In an Exploration of Egg, Part 1, we will explain the basics of cooking eggs. Eggs are one of the most ubiquitous ingredients in the culinary world. Historically, any chef worth their salt has claimed to be able to prepare eggs a hundred different ways. Some theories even maintain that the original toque was created with one hundred pleats to represent the number of ways an egg could be prepared. Wearing a toque implied that the chef possessed the necessary prowess to prepare eggs. Nevertheless, eggs are used in many different fashions by the cooks of today and the best cooks use them individually in sauces, emulsions, foams, and baking.

Preparing Eggs

When it comes to cooking, the process of preparing eggs is a delicate matter. The unique character of the egg is found in its unusual food chemistry. The egg is more complex than it might originally appear. It is composed of proteins and water-primarily, but has several components that make it an interesting ingredient! The shell is primarily a porous, protective layer of calcium carbonate that houses the white (albumen). Albumen is mostly water with some protein — and the yolk — mostly nutritious protein with a little fat and water and a very magical chemical: lecithin (the secret to emulsification).

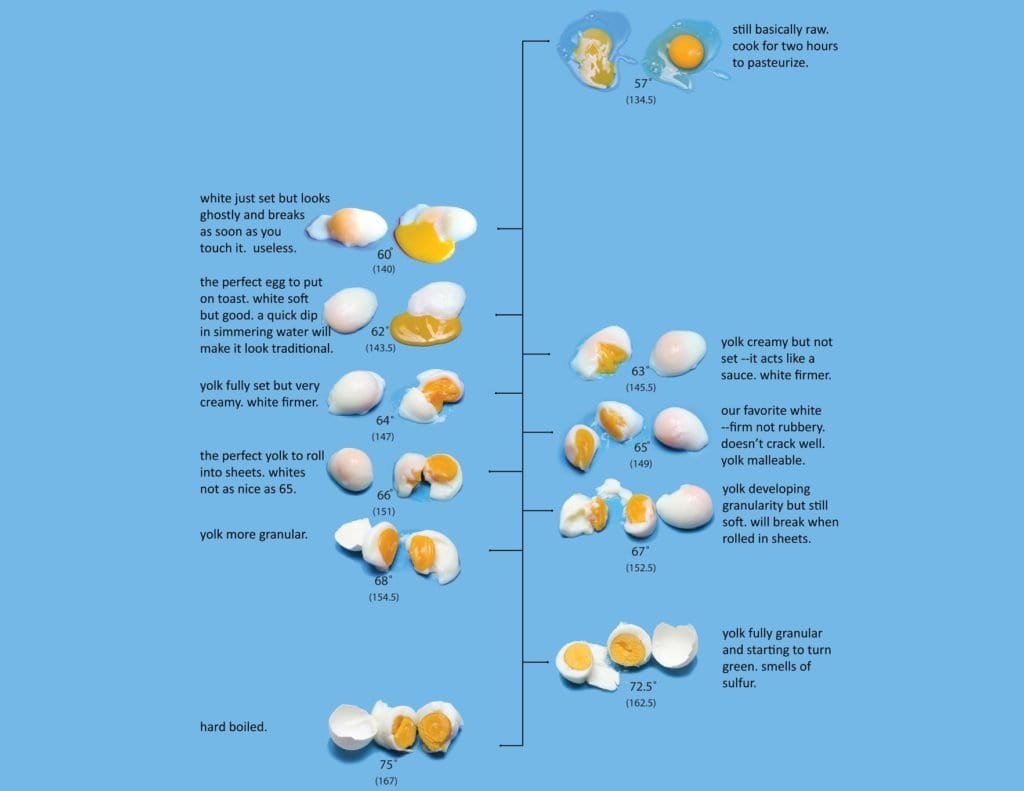

The proteins and the lecithin in eggs contribute both to its versatility as an ingredient and also its stubbornness. Too much heat and your egg is rubbery, not enough whipping and your white is not stiff… Nevertheless, we have found CVap technology to be very good for cooking eggs in all methods. Due to the ability of CVap to maintain and control precise temperatures, we have been able to demonstrate remarkable results in cooking eggs to distinct, precise end-point temperatures.

Cooking Eggs in CVap

We have been working on cooking eggs in our CVap kitchen. The poached egg test graphs below show some of our results from the test runs on pasteurized eggs. We found that 156°F + 2 (new CVap 156°F Vapor Temp/158°F Air Temp) was the best setting for poached eggs in the shell; the yolks were a nice “custard-like” consistency, unlike the 145°F + 0 (new CVap 145°F Vapor Temp/145°F Air Temp) where they hadn’t coagulated as well. Because we know that egg whites typically coagulate between 140°F and 145°F while the yolks coagulate between 145°F and 149°F, the 146°F end temperature for the 156°F + 2 eggs proved to produce a great result. Of course, there are variables to consider (size of eggs, temperature of eggs when placed in the oven, etc.), so you may need to tweak your settings to get ideal consistency.

We will continue to work on eggs and will share those results with you as well. In the meantime, if you have any questions or comments, do not hesitate to contact us.

There are 100 ways to cook an egg, and whether they are center of the plate or part of a cake or custard, there are so many ways to serve them. Check out some of our other egg blogs to learn more.